For the last decade, I’ve lived in the “land of 10,000 lakes,” where wide spans and small shards of water reflect blue skies and flatiron clouds for endless days. Drive in any direction and you’ll pass or cross these blinding mirrors.

While I like the grassy rise above the rock outcrop, my favorite place on the lake where I paddle and take long walks, either alone or in deep talk, is the lagoon where willows dip their leaves and trees hold the light. To get to it by paddle board, I pass beneath the bridge where cars creep along, windows down, and loose scraps of melody fall with wafts of marijuana smoke. Beneath the bridge, it’s darker, cooler, quieter, and the water seems to move more slowly as I pass this threshold and enter the lagoon—the lake’s aside, its parenthesis.

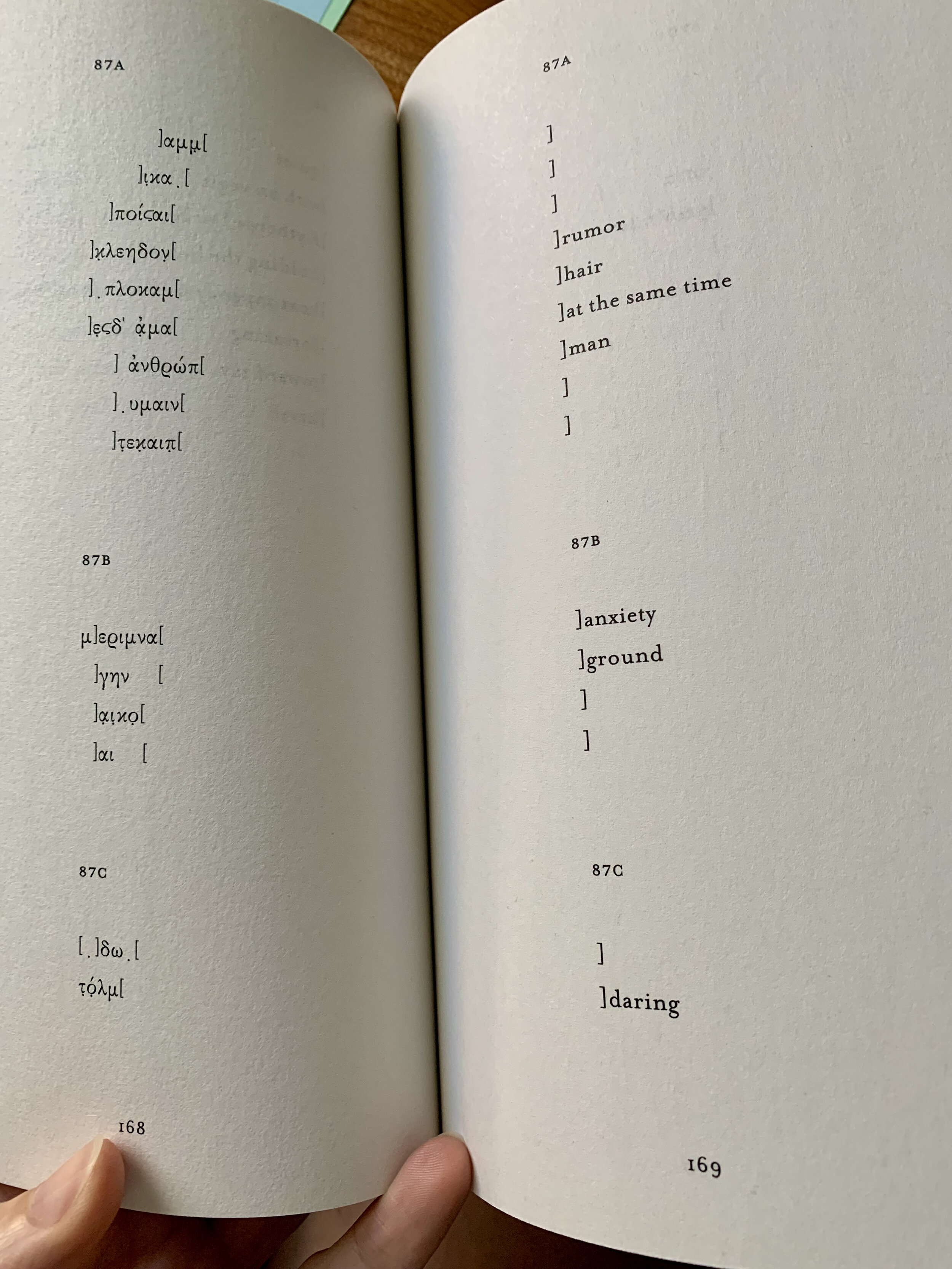

This sense of time and place in brackets in the lagoon is fitting, as lagoon shares a root—lacus, Latin for pond, hollow, opening—with lacuna: an unfilled space or interval, a gap. In the world of books, lacunae are missing portions, emptinesses where words are supposed to be, words unknown even to have existed sometimes, sometimes just unknown, as in Anne Carson’s edition of Sappho’s fragments which has more lacunae—marked by brackets or blank space—than words.

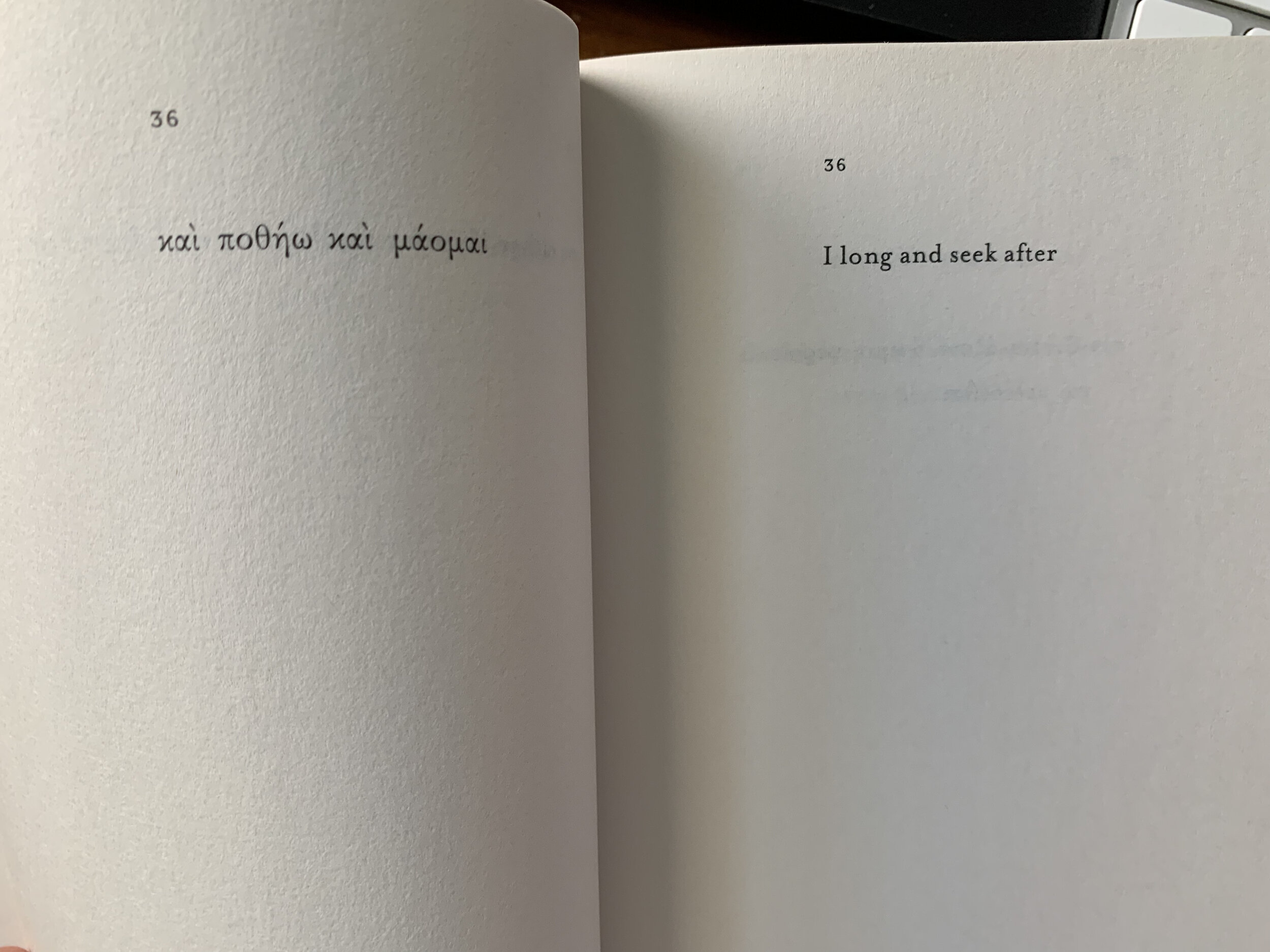

The lacuna in the latter, the object of her longing, actually embodies the experience of longing. The verb “long” derives from langen, from Old German, where the yearning is felt as a growing long, a lengthening toward what one longs for—the feeling one puts into the words “it pulls at my heartstrings,” “it tugs my heart.”

When we long, we think we’re longing for an object, something or someone or some state, like freedom or love. But longing, with its hint of grief, is different from desire, that wish to possess, have, and hold. Longing feels more like what this fragment of a poem by Sappho expresses, lacuna and all: longing is a yearning to incorporate the lacuna, to hold even the hole, to be whole.