A year ago yesterday, I had my last swallow of alcohol. Today marks one year of being sober. What does it mean to be sober?

Etymologically, the word’s root, sobrius (Latin) means “not drunk”—from a variant of se- “without” + ebrius “drunk.”

I like the simplicity of this definition, because all later meanings of the word—“moderate in desires or actions, habitually temperate, restrained”; “calm, quiet, not overcome by emotion”; “appropriately solemn, serious, not giddy”; and “plain or simple in color”—describe states that exist in contrast to intoxication. Because when you’re consuming ethanol and coming down, consuming more, and coming down, you’re swinging on the pleasure-pain pendulum. And if you’re biochemically habituated to it, your mood baseline stays lower, causing you to need more alcohol to raise yourself out of the anxious torpor.

But when you’re not only not drunk but never drunk, this contrast falls away. What I mean is, over this past year I didn’t become plain, solemn, serious, and restrained all the time. Instead, as a non-drinker, I’ve felt all of my feelings more intensely and feel more alive and aware of my moment-by-moment experience.

My heart softened, I became more comfortable in my skin, fear became explicable and tolerable, shame cooled and subsided. Mentally, I quickened. Concentration and creativity come more easily. Most importantly, I realized that intensity isn’t something out there to be found; it comes from the quality of my attention and degree of surrender.

The process has awakened so many insights. It shines a bright light on how normative substance use and abuse is in our culture. I used to claim “I’m a European kind of drinker,” quaffing pinot blanc from Alsace and a grappa on occasion. I went through phases. Where there’s a craft beer scene, I’d find a favorite boutique IPA. My social masks hid from me my real reason for being purple-lipped at a party, relying on rosé to help a friendship flow, or punctuating the phases of an avoidant evening by pulling out different bottles: anxiety. All of the fears, worries, inhibitions, shames, shoulds, and don’ts slipped into soothing, if short-lived, relaxation.

Cheers?

Truth began to pierce the veil in 2019, when I committed to practicing mindfulness in a more disciplined and necessary way than I had before, after having lapsed as a meditator for five years. I knew on some level I was fooling myself, taking the path of least resistance, living mythologically as if I could slip through loopholes and come out closer to perfect. But this level of knowing wasn’t enough to convince me that the very normal style of drinking I was doing was doing nothing good for me.

It took almost three more years, learning to practice self-compassion, and taking some courageous steps that involved breaking with outgrown identities, before I was ready. These were steps through dark, hurting places, across thresholds I feared. Contradictions and inner conflicts tied me up. I knew that one change would help immensely to bring my everyday actions into alignment with my desire to live by my values and make progress on the path to clarity, peace, reality, and love. I had to break the cycle.

Sometimes you hear or read the right thing at the right time. This time, it was the episode of the Huberman Lab podcast “What Alcohol Does to Your Body, Brain, and Health” that convinced me to quit, the day I heard it. My friend Stephanie had been listening to Holly Whitaker’s audiobook, Quit Like a Woman: The Radical Choice to Not Drink in a Culture Obsessed with Alcohol, so I bought it and started listening too. These two productions were all I needed to convince me not only never to poison myself with ethanol again, but also never to accept the false storylines that there’s something wrong with me for being “weak” enough to need to do something so radical as quit, that quitting is shameful and not courageous because it implies I “had a problem,” that I need a drink to be fun, interesting, or relaxed enough to socialize, or that drinking or not drinking is a personal failure. Not drinking “in a culture obsessed with alcohol” makes socializing and fitting in a little harder, but it also clarifies for me how and when I want to socialize and what little value fitting in has.

Of real, lasting, sustaining value are the gifts being sober has brought me:

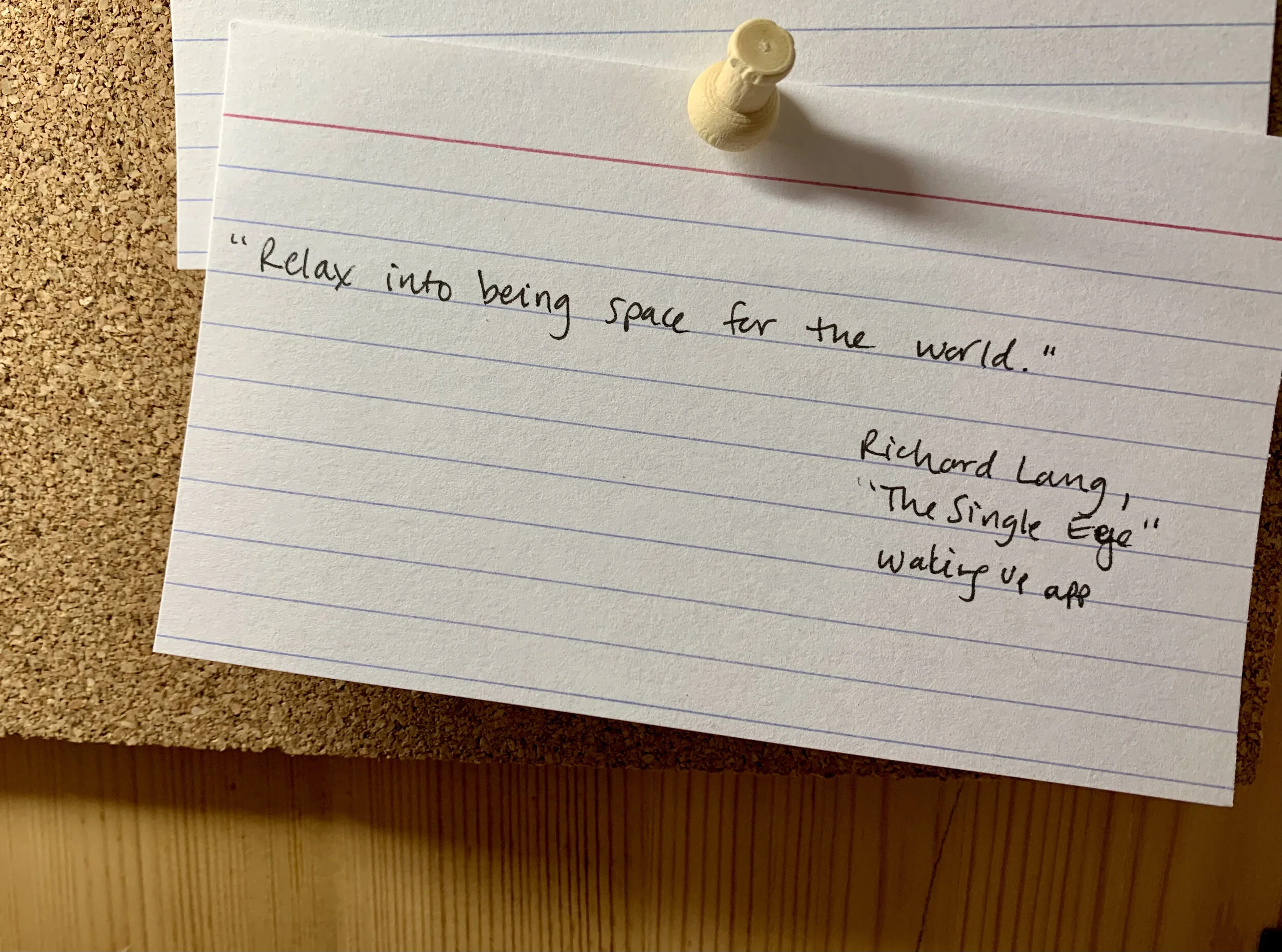

I am vulnerable, naked, alive, and open to all of my feelings; I know anxiety’s signals and now can really practice relaxing around it, knowing that the winds of uncertainty continue to blow because that is life; I catch happiness and joy as they pass and live them intensely for as long as they last;

I never have to suffer through a hangover; I’m more honest, compassionate, courageous, present, and loving; I can really practice the Eightfold Path because my mind isn’t blurred or searching for escape hatches; I know that the intensity, the more I always want, comes through presence with what is really happening in the moment.